On 30 July the church remembers three inspirational men of the 18th and 19th centuries. They are William Wilberforce, social reformer and anti-slavery campaigners Olaudah Equiano and Thomas Clarkson. But who were they?

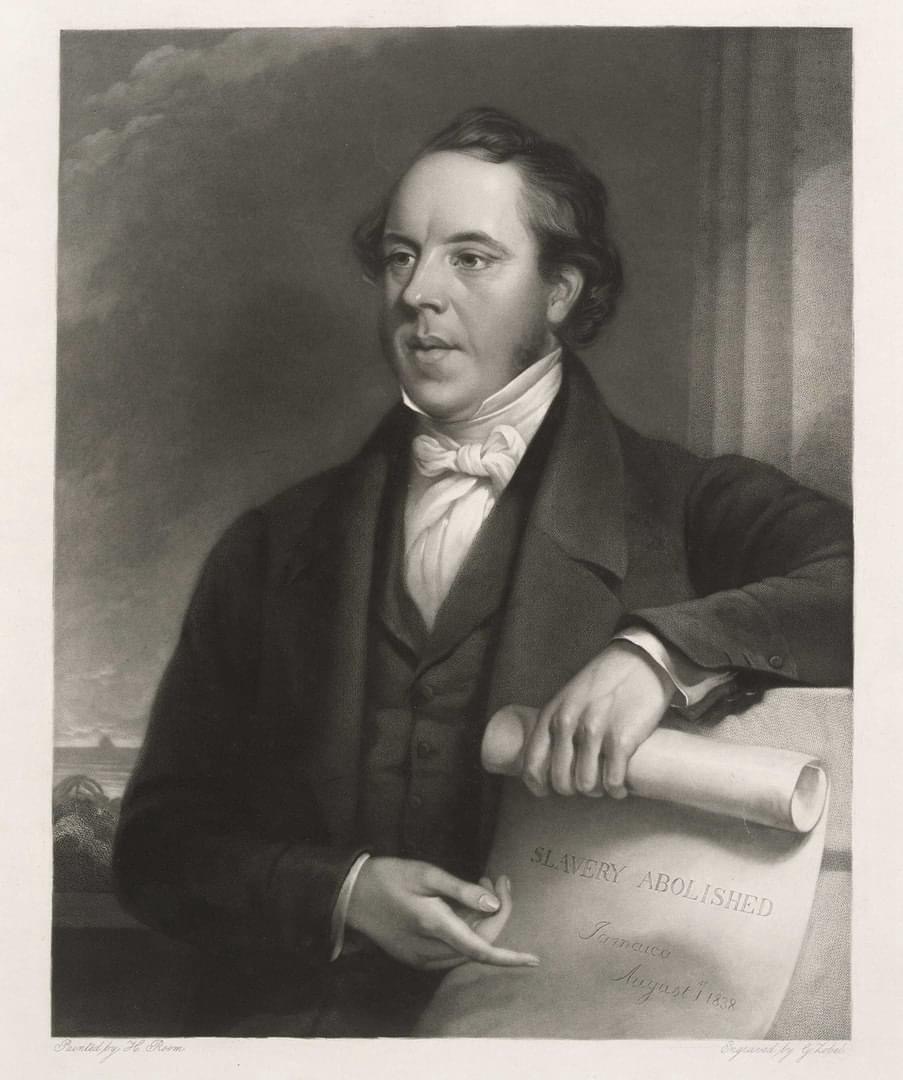

William Wilberforce, Social Reformer, 1759–1833

Born in Hull in 1759, Wilberforce was educated at St John’s College, Cambridge. In 1780 he was elected to Parliament, first for Hull, later for Yorkshire. He was converted to a living faith in his mid twenties, largely through reading William Law’s Serious Call and Philip Doddridge’s Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. Initially he considered taking Holy Orders, but was persuaded by John Newton that he could do more good for the Christian cause in Parliament than in the pulpit.

In 1787 a Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded by Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and a group of Quakers. Needing a Parliamentary spokesman, they approached Wilberforce who immediately saw this as an appropriate sphere of Christian service, commenting that ‘God Almighty has set before me two great objects – the abolition of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.’

In 1791 he moved the first of a long series of annual abolition resolutions in the House of Commons. Not until 1806 did the Commons vote for the abolition of the slave trade. Wilberforce and his influential evangelical friends (known as the ‘Saints’ or the ‘Clapham Sect’ from their place of residence) were involved in promoting a wide variety of causes including the abolition of the state lottery and the opening up of India to Christian missionaries.

Wilberforce supported Catholic emancipation and was involved in the foundation of many societies both to aid the spread of the gospel (Church Missionary Society, Religious Tract Society, British and Foreign Bible Society) and also the ‘reformation of manners’ – attempts to improve the moral tone of English society. These have come under criticism for attacking and abolishing many of the pleasures of the poor yet leaving the rich and influential free to amuse themselves as they pleased.

Though slave trade abolition had come into force in 1807, slavery remained legal in the British Empire and Wilberforce continued to campaign for an end to it, even after ill health forced his retirement from Parliament in 1825. The bill for the abolition of all slavery in British territories passed its crucial vote only three days before his death in July 1833. A year later 800,000 slaves, chiefly in the West Indies, were set free, initially being required to work as ‘apprentices’ for four years for their former masters until they received total freedom in 1838.

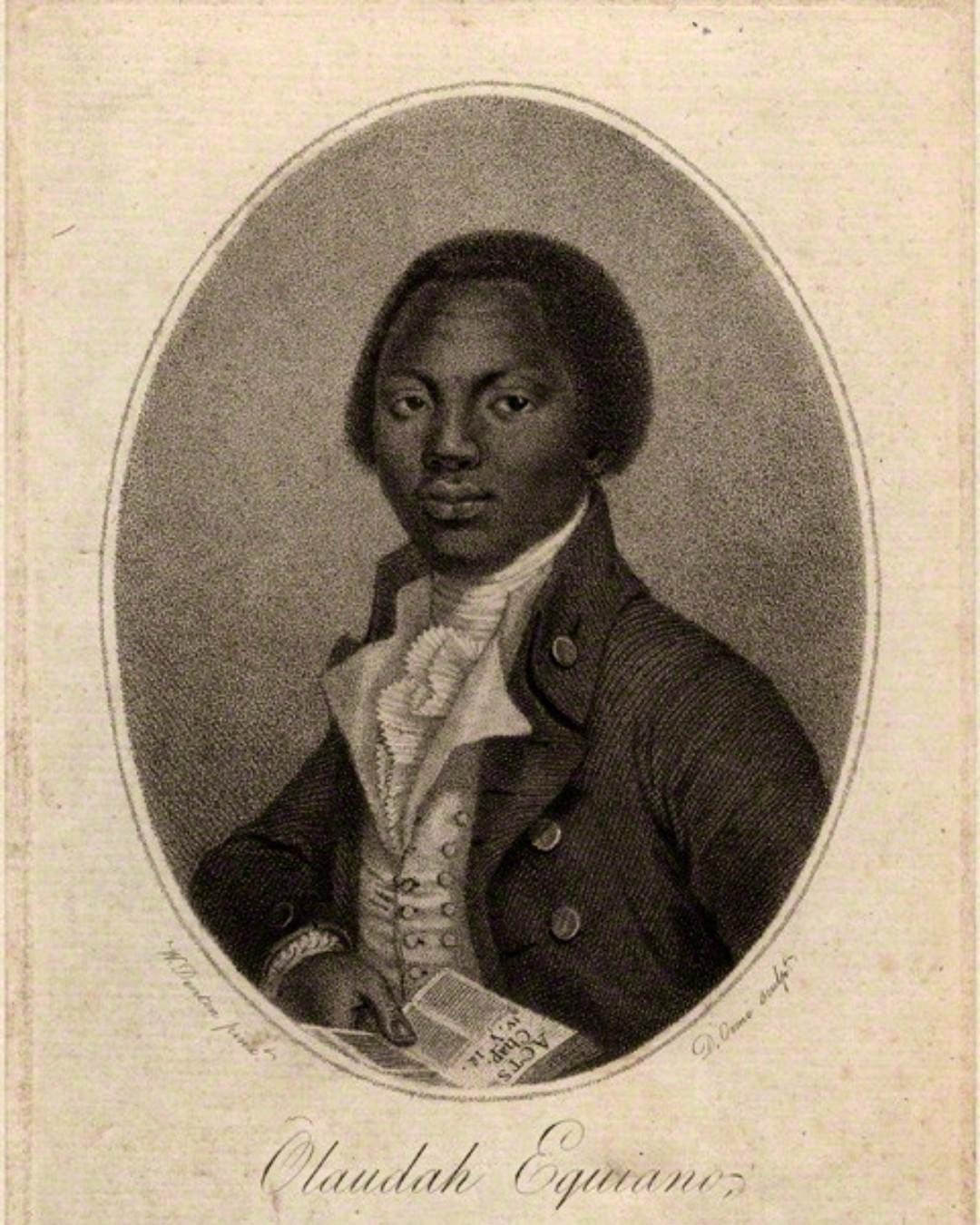

Olaudah Equiano c.1745–1797

According to his autobiography (and there is some scholarly debate regarding its accuracy), Olaudah Equiano was born in Essaka (modern-day Nigeria) about 1745. As a child he was kidnapped and sold into slavery. Transported to America Equiano was first sold to a British naval officer who (according to the normal practice of slave owners changed his name) to Gustavus Vassa.

He observed the cruel treatment of slaves in Virginia but as a naval officer’s slave Equiano received training in seamanship, travelled extensively with his master and even served in the Seven Years’ War (1756–63).

Aware of his potential his master sent Equiano to his wife’s sister in Britain, in order to attend school and to learn to read. In Britain he decided to become a Christian and was baptized at St Margaret’s Westminster in 1759. He later wrote that his Christian faith underpinned all his life’s work.

He was subsequently sold twice until his new master, a Quaker merchant, allowed Equiano to purchase his freedom for the sum of £40 in 1766. As a free man he settled in England and, perhaps inevitably, became involved in the abolitionist movement. Befriended and supported by abolitionists, he was encouraged to write and publish his life story.

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa the African (1789) became a runaway success, helping to advance the cause of the anti-slavery movement in Britain. The book went through nine British editions during his lifetime and many more after his death. Equiano’s personal account of slavery and of his experiences as a black immigrant caused a sensation on publication. The book fuelled a growing anti-slavery movement in Great Britain.

The autobiography (which was updated at each edition) goes on to describe how Equiano’s adventures brought him to London, where he married into English society and became a leading abolitionist. His exposé of the infamous slave-ship Zong whose 133 slaves were thrown overboard in mid-ocean for the owners to claim insurance money, shook the nation.

Equiano’s book became his most lasting contribution to the abolitionist movement, as it vividly demonstrated the humanity of Africans as much as the inhumanity of slavery. He worked to improve economic, social and educational conditions in Africa, and for the poor black community in London. Equiano worked with Granville Sharp to esatblish a colony in Sierra Leone as a home for freed slaves. Having married Susan Cullen at Soham in Cambridgeshire in 1792 they settled in the town and had two daughters. Equiano died in London on 31 March 1797.

Thomas Clarkson 1760–1846

Thomas Clarkson was born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, in 1760, the son of an Anglican clergyman. Educated at Wisbech Grammar School and St John’s College, Cambridge. He graduated in 1783 and was ordained deacon, though he never proceeded to priest’s orders and rarely exercised an ecclesiastical ministry.

Clarkson won a Cambridge University prize for a Latin essay on slavery in 1785. While travelling to London shortly afterwards he experienced a revelation: ‘a thought came into my mind that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end’. This experience and sense of calling ultimately led him to devote his life to the cause of abolition. First he translated his essay into English in order to reach a wider audience. It also acted an introduction to those who were already agitating for the abolition of slavery.

Clarkson joined with a group of Quakers (who had presented an anti-slavery petition to Parliament in 1783) and the Anglican Granville Sharp to form a Committee for the Abolition of Slave Trade. It was Clarkson also approached the young William Wilberforce, who as an Evangelical Anglican and an MP could offer them a link into the House of Commons. Wilberforce was one of very few MPs to have had sympathy with the Quaker petition; he had already put down a Parliamentary question about the slave trade.

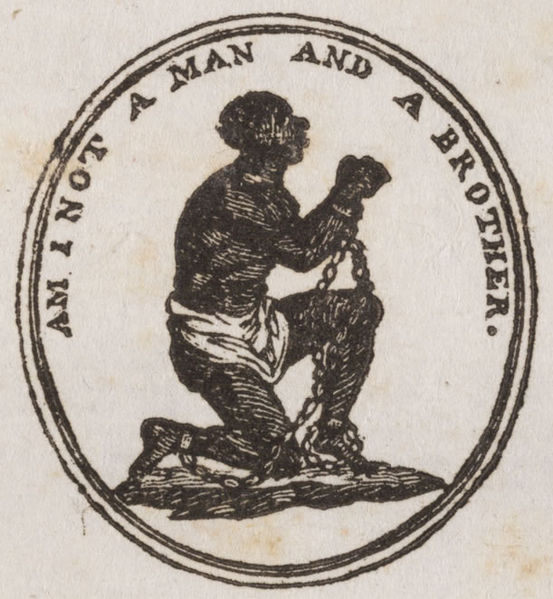

As the anti-slavery campaign swung into action Clarkson became its chief researcher and propagandist, responsible for gathering evidence on the brutality of the slave trade. The campaign, largely based on crowded popular meetings, inexpensive publications and physical evidence such as shackles, whips and models of slave ships, was the first of its kind. So successful were Clarkson’s methods that they were later adopted by the Anti-Corn Law League and proved to be the forerunner of modern political and social campaigning. He is estimated to have travelled 35,000 miles on horseback and on one occasion in Liverpool he was attacked and nearly killed by a gang of sailors paid to assassinate him.

All this took its toll on Clarkson and in 1794 with his health failing he retired from the campaign, married and settled in Suffolk. After recovering is health he returned to the campaign in 1804 and resumed his travelling and campaigning which led to the passage of the Abolition Act by Parliament in 1807. Such was his celebrity that William Wordsworth wrote a sonnet in his honour. But Clarkson did not sit on his laurels.

His subsequent work with Wilberforce and other, younger men such as Thomas Fowell Buxton eventually bore fruit when the Emancipation Act, which ended slavery throughout the British Empire, was passed in 1833. He died on 25 September 1846 at Playford in Suffolk where he was buried in St Mary’s Church. An obelisk to his memory was erected in the churchyard in 1857.

Prayer

God our deliverer,

who sent your Son Jesus Christ

to set your people free from the slavery of sin:

grant that, as your servants William Wilberforce,

Olaudah Equiano and Thomas Clarkson

toiled against the sin of slavery,

so we may bring compassion to all

and work for the freedom of all the children of God;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Extract from Saints on Earth: A biographical companion to Common Worship by John H Darch and Stuart K Burns