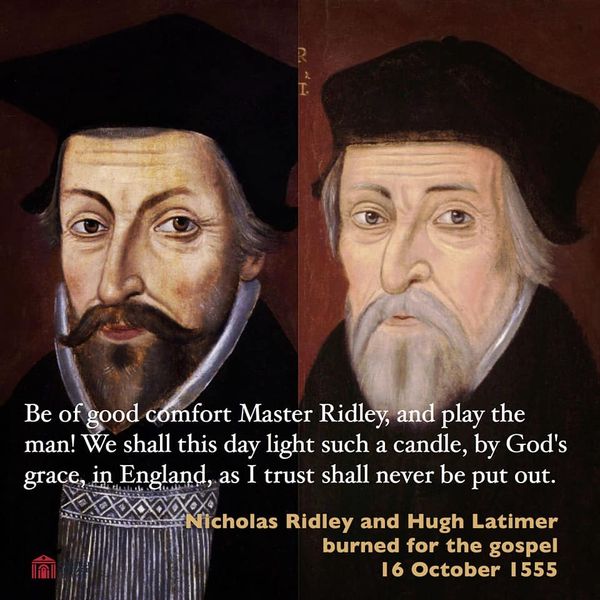

On 16 October the church remembers Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, bishops, martyrs, 1555.

But who were Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer?

Nicholas Ridley (c.1500–55)

Nicholas Ridley was born near Willimoteswyke in Northumberland about 1500, and educated at Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, and the universities of Paris and Louvain. He returned to Cambridge around 1530 where he became known to Thomas Cranmer.

After Cranmer became Archbishop of Canterbury he appointed Ridley as his chaplain in 1537. He became chaplain to King Henry VIII in 1541. On Edward VI’s accession in 1547 Ridley became Bishop of Rochester, being translated to the more important diocese of London in 1550. Ridley helped Cranmer to compile the Prayer Book and Articles and was appointed to help establish Protestantism in the University of Cambridge.

After the death of Edward and with the future of the Reformation in doubt Ridley, along with many other Reformers, resorted to desperate measures and gave his support to Lady Jane Grey as Edward’s successor to the throne and publicly pronounced both of King Henry VIII’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, illegitimate.

Ridley was in the vanguard of the English Reformation in two particular respects. He was the first of the English Reformers to accept and propagate the distinctive teaching on the Eucharist of the ninth-century Benedictine monk Ratramnus. Here the presence of Christ is affirmed but in a spiritual, not physical, form in the hearts of believers receiving the consecrated bread and wine, not in the elements themselves. At a time when Cranmer was still a believer in the (physical) Real Presence, ‘Dr Ridley did confer with me, and … drew me quite from my opinion’. Ridley’s influence on Cranmer was of the highest significance and the distinctive ‘Cranmerian’ flavour of the Prayer Book Communion service thus owes much to Ridley.

As Bishop of London from 1550 Ridley forced the pace of the English Reformation by requiring the removal of stone altars from churches in London diocese and their replacement with wooden communion tables. This was at a time when the political will to move in this direction nationally was lacking and Ridley’s initiative broke the log jam and was widely followed, providing a reformed context for the Eucharist.

When Mary, a Roman Catholic, was proclaimed queen, Ridley was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he wrote statements defending his religious opinions. In 1554, refusing to recant, he was declared a heretic and excommunicated, and in 1555 he was tried and condemned for heresy. Ridley was burned at the stake in Oxford along with Hugh Latimer on 16 October 1555.

Hugh Latimer (c.1485–1555)

Born the son of a yeoman farmer at Thurcaston in Leicestershire about 1485, Hugh Latimer was educated at Cambridge and elected Fellow of Clare Hall in 1510. After ordination he quickly gained a reputation as a highly able speaker and preacher and used these gifts to promote reform of the university and social justice on a wider scale.

Cambridge was a hotbed of Protestant opinions and in the early 1520s Latimer began to align himself with them. When required by the Bishop of Ely to preach a sermon against Martin Luther, he refused and was for a time suspended from preaching. He regained his licence to preach after a successful interview with Cardinal Wolsey. Latimer’s preaching style was direct, homely and witty, demonstrating a clear knowledge of both Scripture and human nature. He preached before Henry VIII in Lent 1530 and the king’s favour was demonstrated by Latimer’s presentation to the living of West Kington in Wiltshire. But as Latimer’s preaching and doctrine became unmistakably Protestant he received a censure from Convocation in 1532.

After the break with Rome, however, Latimer’s advice was increasingly sought by the king and in 1535 he became Bishop of Worcester. He resigned the see four years later when the king turned against reform and the conservative Act of Six Articles was enacted. In great danger at this time, Latimer was imprisoned for some months then forbidden to preach and required to leave London.

By the end of Henry VIII’s reign he was imprisoned in the Tower, but was released on Edward VI’s accession and once again became a popular and influential court preacher, still with an emphasis on justice as he denounced both social and ecclesiastical corruption and abuses.

On the accession of Queen Mary in 1553 he was again imprisoned. After refusing to recant his theological opinions he was condemned and burnt with Ridley at the same stake in Oxford on 16 October 1555.

Ridley went to the pyre in a smart black gown, but the grey-haired Latimer, who had a gift for publicity, wore a shabby old garment, which he took off to reveal a shroud. Ridley kissed the stake and both men knelt and prayed. After a fifteen-minute sermon urging them to repent, they were chained to the stake and a bag of gunpowder was hung round each man’s neck. The pyre was made of gorse branches and faggots of wood.

Whether Latimer did indeed comfort the younger and more fearful Ridley with the words recorded by John Foxe is not known, but they have nevertheless entered into Anglican folklore:

Be of good comfort Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England, as (I trust) shall never be put out.

As the fire took hold, Latimer was stifled by the smoke and died without pain, but poor Ridley was not so lucky. The wood was piled up above his head, but he writhed in agony and repeatedly cried out, ‘Lord, have mercy upon me’ and ‘I cannot burn’.

A Prayer

Keep us, O Lord, constant in faith and zealous in witness,

that, like thy servants Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley,

we may live in thy fear, die in thy favour, and rest in thy peace;

for the sake of Jesus Christ, thy Son our Lord,

who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost,

one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Revd Paul A. Carr and extract from ‘Saints on Earth: A biographical companion to Common Worship’ by John H Darch and Stuart K Burns

Such a volatile time to live and have a faith. All the Tudors were ‘bloody’ not just Mary! I’m not sure how early Protestantism would have reached Britain if not for the Reformation. For a number of years even non conforming Protestants were killed. Thank you for the article and the reminder of how dedicated these men were to their beliefs.

LikeLiked by 1 person